Ladder of Inference to Minimize Misunderstandings

How many times have you acted on an assumption that turned out to be wrong? It happens all the time. Several weeks ago, in the early aftermath of the Marathon Bombing tragedy, I found myself believing that my younger brother, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, was a solely victim of his brother’s violence.

How many times have you acted on an assumption that turned out to be wrong? It happens all the time. Several weeks ago, in the early aftermath of the Marathon Bombing tragedy, I found myself believing that my younger brother, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, was a solely victim of his brother’s violence.

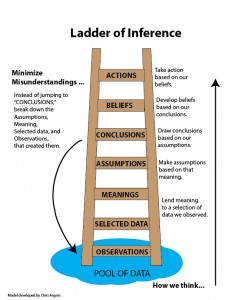

The Ladder of Inference

As I consider this mistaken belief through the lens of the Ladder of Inference, I see that in the “Pool of Data” (available to me as a resident in suburban Boston), were the reports from Dzhokar’s high school friends, who vouched for his good character. I “selected that data,” lent meaning to its significance, and came away with “assumptions” that led to my belief.

We draw conclusions all the time, sometimes not even considering their origin until we run into misunderstandings. Consider your reaction if you see someone cross their arms and look abruptly away from you. You might conclude that they are disinterested and disrespectful, and decide to cut them off from future communication. Alternatively, if you were to engage in a conversation and discuss the observations that led to your conclusions, you might uncover additional data, such as whether they felt a cold breeze, crossed their arms because they were shivering, and looked away to see if a window had been opened.

The Ladder of Inference, originally developed by Harvard Business School professor Chris Argyris, helps us understand our communication barriers and come to a common understanding based on shared data and interpretation. It is a wonderful tool if you’re teaching communication and soft skills workshops, but it’s also a great tool to use as a teacher or trainer, to better understand the thinking of your students or colleagues.

Read more about the Ladder of Inference.

- +29

Comments